Atropine has emerged as a popular treatment for myopia; however, a new study has reported that a placebo group enjoyed more efficacy than subjects treated with low-dose atropine.

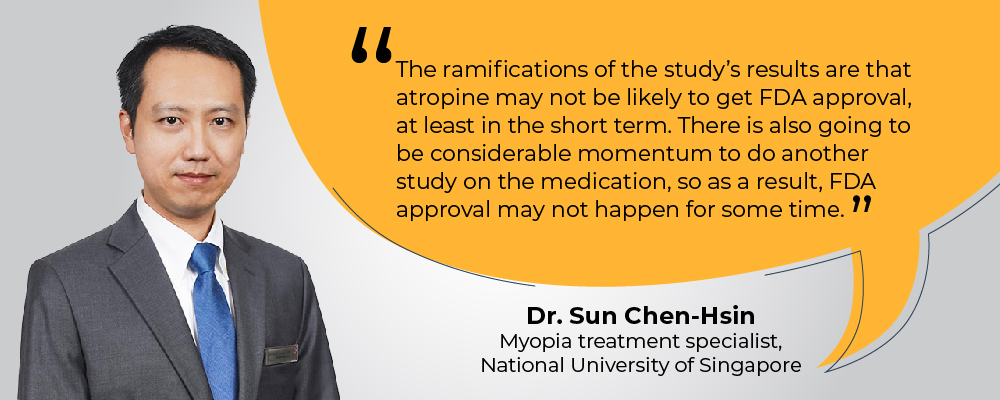

We spoke with Dr. Sun Chen-Hsin, a leading myopia specialist based in Singapore, about the results of the study, what they mean for patients, and the future of atropine treatment.

Coming to an unexpected result is a common experience when carrying out a research project; however, a conclusion that causes real surprise among one’s colleagues is relatively rare. Even more so when the results in question could cause a drug’s approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to be delayed.

The authors of Low-Dose 0.01% Atropine Eye Drops vs. Placebo for Myopia Control may not have expected to generate a minor furor when they set out with their study. The project was run as a randomized placebo-controlled, double-masked clinical trial from June 2018 to September 2022. Children aged five to 12 years were recruited from 12 community and institution-based practices in the United States. All participants had low to moderate bilateral myopia −1.00 to −6.00 diopters.1

The study’s concluding remarks, however, were shocking in their starkness: “The results do not support the use of 0.01% atropine eye drops nightly to slow the progression of myopia in US children.”

In fact, the study went even further than this. The investigators found that children in the placebo group reported better results than their counterparts in the atropine cohort, and that atropine at this dose doesn’t slow myopia progression or axial elongation in US children.1 Furor sparked indeed.

Compare, contrast and confirm the results

But in order to understand this seeming setback for atropine advocates, myopia expert Dr. Sun Chen-Hsin of Singapore’s prestigious National University Hospital believes context is needed. “The 0.01% atropine study was published on the JAMA Network, a reputable organization sponsored by the National Institute of Health, and it has a fairly standard design. At first glance, you would not think that there is a problem with it. But if you examine it in more detail, you can explain the surprising results,” explained Dr. Sun.

When Dr. Sun first read the results of Low-Dose 0.01% Atropine Eye Drops vs. Placebo for Myopia Control he was one of the many surprised at low-dose atropine’s poor performance. There was, however, something familiar about the methodology behind the study that made him wonder how its results were ultimately confirmed. Dr. Sun realized that he had seen a similar study that would help explain why the placebo group could have been more effective than the atropine cohort.

The Efficacy and Safety of 0.01% and 0.02% Atropine for the Treatment of Pediatric Myopia Progression Over 3 Years was published just over a month prior to the more recent study focused only on .01% atropine. The two studies may be similar, but, as mentioned, the more recent study recorded a stronger result for the placebo group. On the other hand, the combined study found evidence for the efficacy of the 0.01% dosage.2 Dr. Sun wondered what could account for the difference.

He found that the answer lay in the second group surveyed in the slightly older study. That was because this research project also examined patients who received eye drops at a concentration of 0.02%, which recorded poorer results than both 0.01% – and more crucially, the 0.00% group.

This struck Dr. Sun as odd, especially as the 0.01% cohort had performed well. Examining the newer study to discover why this was the case, he concluded that the disparities were due to differences in the baseline sample characteristics, especially as the older study’s participants had a larger age range, from three up to 16 years old.2

Age, ethnic background, and time spent outdoors

“When you have an age range that is that huge then the progression for these kids is going to be very heterogeneous, as a 16-year-old is not going to progress as much as a three-year-old. You can try to match the placebo group and treatment group so that they have the same average age, but the bracket of the number of participants in each age group will not be the same,” Dr. Sun said.

This led Dr. Sun to investigate the baseline statistics of the newer study that examined 0.01% atropine alone over three years and he realized why the placebo performed more effectively. His first discovery was that the age group was not as wide as the previous study (the enrolled participants in the 0.01% and 0.02% atropine study were 3 to 16 years of age versus the 0.01% atropine study alone which was conducted on children aged 5 to 12 years only), which would make a positive result for atropine less likely.

The 0.01% and 0.02% atropine study, despite being primarily carried out primarily in the United States and the United Kingdom, had a higher share of East Asian participants, at 50%. Dr. Sun believes this may have skewed the results of the study as this ethnic group is significantly more likely to experience myopia. However, he emphasized that this should be seen as a contributing, rather than a definitive, factor.

Dr. Sun believes that the main issue with these atropine studies was that they did not take into account lifestyle factors, like time spent outdoors and the amount of time spent per day looking at computer screens, which have both been proven to have a direct link to myopia progression.3 Both studies were also conducted throughout the COVID-19 pandemic in countries that underwent strict lockdown procedures. During this time, patients would have become more susceptible to myopia, as they were stuck inside and more frequently glued to electronic devices.

Fears for atropine’s acceptance by the FDA

Dr. Sun remains a proponent of atropine, pointing to a considerable body of research that supports its efficacy. He also reports his own anecdotal experience of using the medication in a case involving a six-year-old child who developed myopia in one eye (with a diopter of -0.1), for whom he prescribed 0.01% atropine.

The child’s other eye began to develop myopia; however, the parents decided (erroneously, in his opinion) to only treat the original eye with atropine. Within six months, the original eye remained at the same level, whereas the untreated myopic eye had reached a diopter of -1.5.

He is concerned, however, that a placebo being recorded as more effective than atropine in one study could prove to be a major stumbling block toward its full acceptance by international ocular healthcare. The issue is particularly acute as the medication is currently being considered by the FDA for full approval.

“The ramifications of the study’s results are that atropine may not be likely to get FDA approval, at least in the short term. There is also going to be considerable momentum to do another study on the medication, so as a result, FDA approval may not happen for some time,” Dr. Sun explained.

“Many countries look to the FDA for guidance in terms of approval for their local market. So if there is no FDA approval, then a lot of countries will just not want to use atropine,” he concluded. Bad news for atropine fans for now, as this battle appears to have been lost. But the war over the drug’s future in myopia control regimens is ongoing, as great interest in the drug’s efficacy promises a steady churn of new data.

References

- Repka MX, Weise KK, Chandler DL, et al; Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Low-Dose 0.01% Atropine Eye Drops vs Placebo for Myopia Control: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023;141(8):756-765.

- Zadnik K, Schulman E, Flitcroft I, et al; CHAMP Trial Group Investigators. Efficacy and Safety of 0.01% and 0.02% Atropine for the Treatment of Pediatric Myopia Progression Over 3 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023;e232097. [Online ahead of print]

- Lee SS, Mackey DA. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Myopia in Young Adults: Review of Findings From the Raine Study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:861044.