India has taken a hard stance in its fight against eye disease. However, access to treatment and testing opportunities vary widely across the country; further, eye care professionals (ECPs) can find difficulty in standardizing, funding and educating the population on the public health risks of eye disease. Causes of preventable blindness in India have financial, psycho-social and regional limitations.

Eye Care Access Across the Country Varies

Access to optometric treatment varies greatly across the vast nation of India, which has both bustling urban centers and small rural villages. There is significant situational and economic diversity as well — this lends itself to broad differences in the prevalence and treatment of myopia, hyperopia and astigmatism.

Dr. Shaveta Bhayana from the department of ophthalmology at the Government Medical College Hospital in Chandigarh, India, said: “The difference between cities and villages is significant. The awareness level of village populations and the infrastructure provided at the sub-district level is comparatively low.” These differences are large problems facing ECPs in modern India.

Knowledge of Optometry in the General Population

There may also be a lack of understanding of the nature of optometry in the general population. According to a 2020 study, many optometry students did not understand the true scope of optometry until they entered their programs: “Students recalled that they had limited information about optometry when they enrolled in the course.” Some students believed they would be only dispensing eyeglasses, while others thought that they would be something like an ophthalmological assistant. Only those students who had first-hand experience with optometry knew what to expect from the program, noted the authors.1

These opinions are indicative of a larger issue. If optometry students are unsure about the parameters of the practice, then a large portion of the population is most likely also unaware of the nature of optometric vision testing and treatment.

Dr. Bhayana said: “In my opinion, in the population I work with, I have seen people ignore their eye problems a lot. Presenting to the OPD with mature cataract and late stage glaucoma is very frequently seen.” Ignoring eye problems of varying severity is one social-psychological reason for the prevalence of eye disease in India.

Psycho-Social Impacts on Spectacle Compliance

There are many reasons why people fail to comply with suggested treatment. A study published by the Indian Journal of Optometry in 2018 claimed that the main barriers to treatment compliance are psychosocial, financial and social.2

The study noted that in some situations, the spectacles themselves can be a barrier to proper treatment. Because there are not enough resources in some areas, “lack of frame measurements and consequential discomfort was a major reason attributed by ECPs for poor spectacle compliance.” The study authors also shared that many patients lacked a safe place to store their spectacles, or would be severely punished by parents if “they lost or misplaced their spectacles and hence, tended not to use them.” Therefore expense and necessity of spectacle wearing can be lost to childhood irresponsibility and/ or fear of punishment.

Finances are also limiting. According to the authors, “service providers added that recurring costs of replacing broken or damaged spectacles was burdensome to many parents on account of their poor socioeconomic status.”

Dr. Bhayana agreed: “Access to a health care center along with financial constraints makes them unable to visit the hospital.” In this way, household obligations and financial restrictions prevent many people from seeking optometric aid, let alone comply with treatment recommended by ECPs.

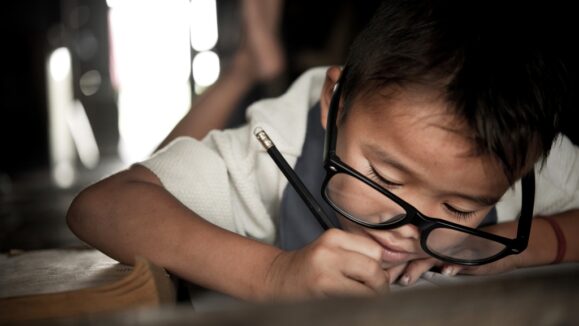

The reluctance to comply with treatment also has social roots. It’s not surprising that school children are more concerned about fitting in with their peers than their eye health. The study continued that “social workers highlighted feelings of loneliness and inferiority experienced by children who felt embarrassed to wear spectacles in front of others.’’ This is because children often worry about acceptance by their peers. There are also concerns of parents regarding marriage prospects for young girls who wear spectacles. Boys, in turn, were worried about not being allowed to play on account of wearing spectacles. And there is additional social stigma against those who wear glasses, that is perpetuated by the media. This aversion may impact the progression of myopia and prevalence of treatable blindness. It is important that ECPs and lens manufacturers work hard to educate and dispel negative stigmas around wearing spectacles.

Plans for the Future of Eye Care

However, the future looks bright for limiting preventative blindness. The North Indian Myopia Study (NIMS)3 conducted a series of vision tests at 20 different schools in Delhi. Their goal was to properly identify the prevalence of refractive issues, compare them to other populations, and make recommendations for the future of vision testing.

According to NIMS: “In India, the School Vision Screening Programme, part of the National Programme for Control of Blindness, is an important strategy for controlling visual impairment due to refractive error.” The authors of the study stressed the importance of early and regular vision screenings in the future to slow instances of high myopia in India. Though this study is focused in the urban area of Delhi, frequent vision testing as prevention is also necessary in rural areas.

Dr. Bhayana also agreed. She said: “Mandatory school screening camps and access to the elderly population should be increased.” There are ways to improve access to eye care to underserved populations and it’s necessary for ECPs all over India to focus attention on increasing testing and general access to treatment to improve the eye health of the entire population.

India’s ECP community has made it clear that eye disease is a national health risk. Social, financial and limits of access to eye care centers are all major factors that contribute to treatable blindness. However, there is an active movement in India to increase access and knowledge of eye disease and treatment. It is evident that the increases in testing and access to treatment are continually rising and the future of optometry in India will only improve past existing advances.

References

- Venugopal D, Lal B, Shirodker S, Kanojiya R, Kaushal R. Optometry students’ perspective on optometry in suburban Western India: A qualitative study. J Optom. 2020;S1888-4296(20)30009-1.

- Narayanan A, Kumar S, Ramani KK. Spectacle compliance among adolescents in Southern India: Perspectives of service providers. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66(7):945-949.

- Saxena R, Vashist P, Tandon R, et al. Incidence and progression of myopia and associated factors in urban school children in Delhi: The North India Myopia Study (NIM Study). PloS one. 2015;10(2):e0117349.