We don’t typically think of the eye when we think of muscles. Usually we think about the ones we see first: the biceps, abs, glutes and deltoids. These muscles are splashed across the covers of health and fitness magazines, as well as films, television and social media. They’re the ones that get all the attention.

After those most visible of muscles, we might think about other ones like the tongue or the heart. These are the less obvious muscles, the ones we rarely or never see. Even if we’re not thinking of them as such, these are muscles too. Wherever something is moving or causing something to move in the body, there are muscles involved somewhere.

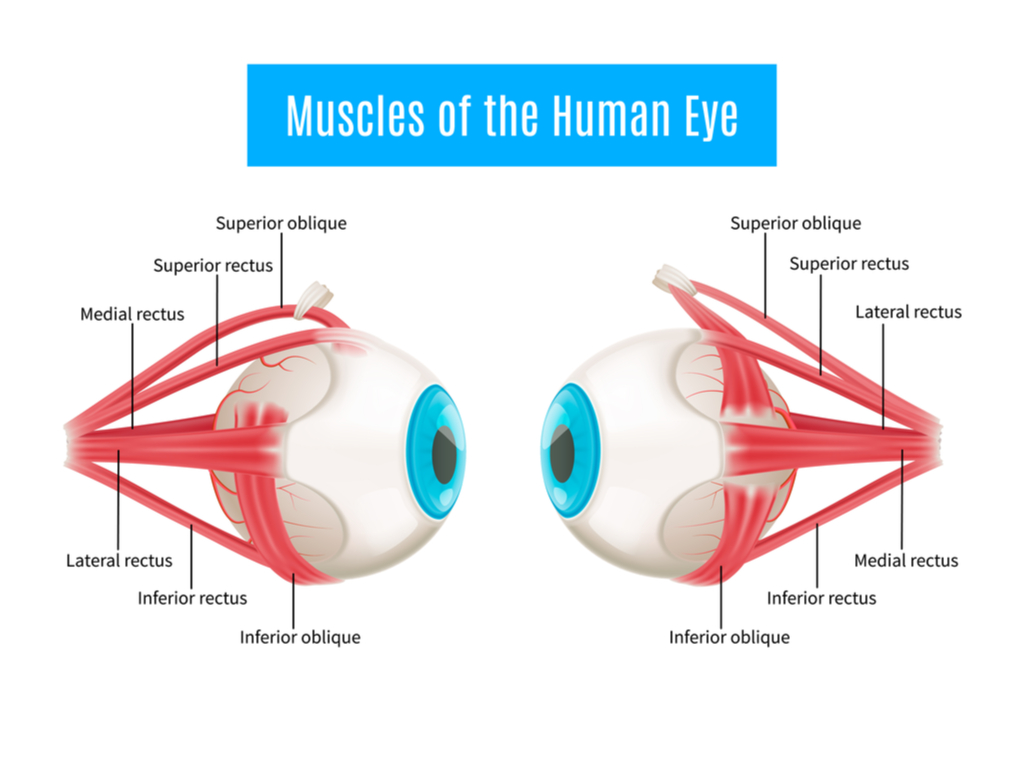

As few parts of the body do as much moving as our eyeballs do, it follows that there are some pretty active muscles at work around them, powering every glance and every roll of the eye, and moving your focus across these words on your screen right now. And yes, the eye does have muscles — six of them, to be exact. They don’t often get a lot of attention, in large part because we can’t see them. And if you can’t see something, and it’s not broken, you tend to forget it’s there.

But — just like many other forgotten yet essential body parts — these eye muscles can sometimes develop problems. And when these muscle problems develop, it can sometimes be very serious business. When the eye muscles (properly called extraocular muscles, as they’re attached to the outside of the eye) misbehave in a way that interferes with our normal activities, it’s time to consult an eye care professional.

A Quick Roadmap of the Extraocular Muscles

The American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus (AAPOS) provides a descriptive and pictorial explanation of the extraocular muscles and how they interact with the eyeball in order to move it.

Each of the extraocular muscles originates in the eye socket, and moves the eye in a different way. The superior rectus moves the eye upward from the top of the eye, while the inferior rectus moves it downward from the bottom. On the side of the eye, the medial rectus attaches near the nose and moves the eye toward the center of the face. On the outside, the lateral rectus attaches near the temple and moves the eye outward.

In addition to the fairly straightforward rectus muscles, the last pair — the superior oblique and inferior oblique — complete the eye’s full range of motion. These muscles attach to the anterior position of the sclera, and assist in rotational movement of the eye, along with the rectus muscles. They also maintain a level field of vision when the head is turned by keeping the eyes balanced horizontally.

Just as is the case with our hands, none of these muscles operate independently of one another, but create a seamless cohesion of movement for the eyeball. Similarly, we do not experience the sensation of using any one of these muscles, even though their movement is relatively constant in our daily lives. Until something goes wrong with these muscles, we simply take them for granted.

Vision Problems in a Child’s Eyes

While a great many health care issues that lead to eye surgery do not occur or become symptomatic until later in life, and frequently require diagnosis by an ophthalmologist in order to be discovered, this is not typically the case in the conditions that call for eye muscle surgery. Rather, these highly treatable conditions are frequently noted when patients are young children, at which point efforts to correct them can begin swiftly.

There are many reasons for this. To begin with, misalignment of the child’s eyes, a key characteristic of extraocular muscle problems, is very noticeable to a patient and to their parent. It is usually readily apparent that there is a problem with a child’s eye alignment, and parents are quick to seek eye care for their children.

Along these same lines, pediatric eye screenings are far more common than they are among adults. Older children as well as young children undergo regular outpatient vision check-ups in order to screen them for eyeglasses and to detect any vision loss that may be occurring. Thus, the very detectable misalignments and other signs of extraocular muscle problems are frequently detected in pediatric patients.

Additionally, while other surgical procedures, such as cataract surgery, become necessary due to the break down of the eye’s structures as we age, this is not usually the case with eye muscle surgery. While injuries to the eye muscle can come about due to external factors, eye misalignments and other conditions requiring this surgery often occur independently.

Strabismus Surgery: Preserving Binocular Vision With Eye Muscle Surgery

By far the most commonly occurring condition leading to eye muscle surgery is that of strabismus. Commonly known as crossed eyes, strabismus is a misalignment of the eyes. Typically, this involves one of the eyes pointing straight toward its focus, while the other, affected eye points in a different direction. This eye misalignment can be inward, whereby it is referred to as esotropia, or outward, when it is called exotropia.

The visual appearance of crossed eyes is the most apparent symptom of strabismus. In addition, the lack of visual acuity caused by this misalignment can lead to uncoordinated eye movements, loss of depth perception, and in severe cases, double vision. It is this double vision that is of greatest concern with pediatric patients, as this can lead to diminished neural receptivity from the weaker of the two eyes. This can ultimately compromise the patient’s binocular vision.

Strabismus does not always require eye muscle surgery. It often occurs in infants, but frequently resolves itself within 3 months as the young child’s muscles continue to develop, thereby correcting the problem. Other times, when this does not happen, eye care professionals will try to correct the problem with glasses, eye strengthening exercises, and eye patches.

Frequently, however, ophthalmologists elect to perform eye muscle surgery in order to address strabismus. Various surgical procedures are available to correct this condition. The outpatient procedures are relatively quick ones, taking anywhere from 45 minutes to 2 hours. The patient is usually placed under general anesthesia (particularly in pediatric procedures) and able to be taken home the same day.

The first of these — recession — seeks to weaken the muscle that is pulling the eye too strongly in one direction. This is achieved by identifying the extraocular muscle whose tension is causing this misalignment. The surgeon detaches this muscle from the sclera, and reattaches it with a suture in a different part of the eye, leaving the muscle in a more relaxed position. This serves to reduce the resting tension of the muscle, allowing for more balanced alignment of the eye.

The second such surgical procedure — resection/plication — does the opposite of recession. Rather than releasing the tension on the stronger extraocular muscle, resection/plication aims to strengthen the tension of the weaker muscle. In a resection, this is achieved by detaching the muscle from the sclera, shortening it, and reattaching it with sutures. Plication achieves the same correction, but does so by folding the muscle tissue rather than removing it.

Both of these procedures are performed by creating a small incision in the conjunctiva, the mucous membrane that covers the eye and eyelid, and then proceeding to perform the appropriate removal and reattaching of the muscles to the eye. Antibiotic eye drops are typically administered after the procedure, and sometimes a few days later.

Following the general procedure, some ophthalmologists prefer to use an adjustable suture in order to ensure correct eye alignment. An adjustable suture is a temporary knot at the site of the muscular reattachment to the sclera. It allows for coordinating the tension with the reported visual acuity of patients able to cooperate in assessing their vision, usually adult or older children. This coordination is performed under local anesthesia in a separate session subsequent to the initial procedure.

While strabismus surgery is minimally invasive, and has a relatively high success rate of 60-80%, it is not without its difficulties. Though postoperative pain is minimal and can be managed with over-the-counter remedies like Tylenol, there is a small risk of ocular swelling or higher levels of discomfort. Though it is usually quite unlikely to cause complications elsewhere in the eye, some studies have shown that strabismus surgery may be linked to retinal detachment.

Other Bases for Eye Muscle Surgery: Amblyopia and Nystagmus

Though strabismus surgery is by far the most common eye muscle surgery performed, there are several similar and sometimes related conditions which can lead an ophthalmologist to consider surgical procedures.

Amblyopia is one such condition, and one that can be caused by strabismus. Just as strabismus has its colloquial name of crossed eyes, so too does amblyopia, which is commonly known as a “lazy eye.” The eye, whose function is diminished, can sometimes drift inward or outward, and away from its point of focus.

When strabismus goes untreated, and a dominant eye takes over, the weaker eye can begin to deteriorate through lack of use. One of the long-term consequences of this is amblyopia. While a number of treatments are available, including some boldly creative ones involving video games and virtual reality, surgery is sometimes the only effective way forward.

Surgery for amblyopia is quite similar to that used to treat strabismus, with resection being particularly helpful in reintroducing muscle tension to the extraocular muscle that has lost its capacity to maintain it on its own.

Another condition sometimes treated by eye muscle surgery has the appearance of being the opposite of amblyopia. While the eye appears lazy in patients with amblyopia, nystagmus patients have the appearance of hyperactive eyes, which move and twitch involuntarily.

While nystagmus remains something of a mystery in the field of eye care, with its causes and treatments little-understood, surgery is sometimes used in order to give patients better control over their eyes.

Here, again, the procedure is relatively similar. Recession is performed with the aim of reducing muscular tension on the eye, and allowing the muscle to relax, thereby minimizing or eliminating involuntary movement.

One of the Most Treatable Areas of the Eye

As ailments of the eye are so often irreversible, it is good to know that treatments with high success rates are available for areas like eye muscle surgery. As always, early detection is key, and as patients for this type of surgery are often children, it gives us a leg up in preventing long-term damage.

While new and exciting noninvasive treatments come out every day, it is a relief that eye muscle surgery is such a reliable and effective option for patients who need it.