Workforce shifts haven’t kept Americans from getting closer to ophthalmologic care

The map of American eye care is changing. Once defined by long drives and sparse specialists, the landscape is closing in mile by mile. A new analysis shows that even as optometrists gain more surgical ground, ophthalmologists are now closer to patients than ever before.

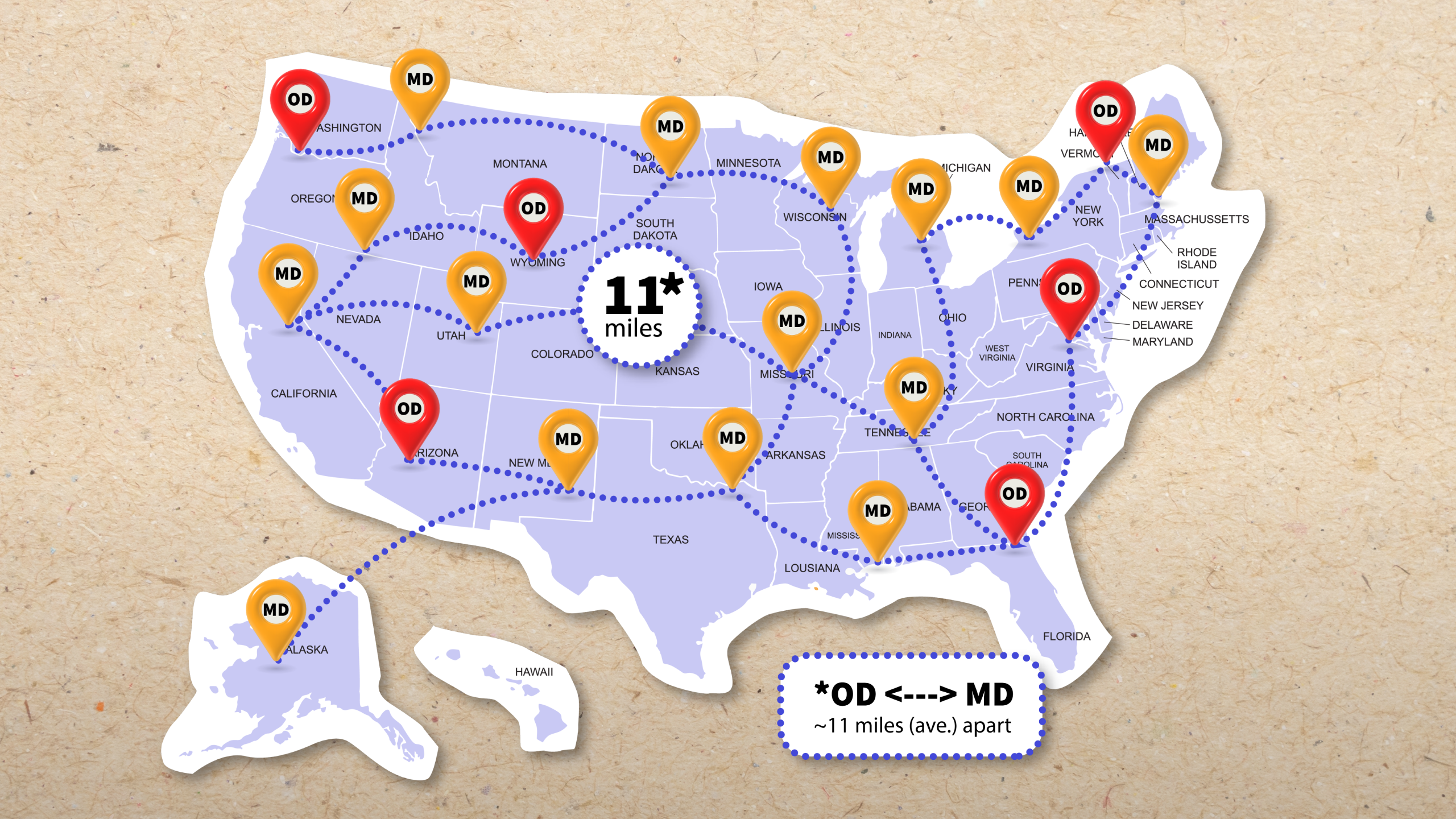

Researchers at Tulane University (New Orleans, LA) found that although the number of ophthalmologists (MDs) nationwide declined slightly between 2014 and 2024, their practice locations expanded dramatically, improving access across nearly every U.S. zip code.1 The findings arrive just as more states push to expand optometrists’ (ODs) surgical privileges, often citing geography as the reason.2

Narrowing the gap

The eye care map is filling in. Over the past decade, ophthalmology practice sites increased by 60%, while optometry practices rose by 44%. Zip codes once served solely by optometrists are shrinking and the average drive from an OD office to an MD one is now just 11 miles, down from 12 a decade ago.1

Lead author Dr. Peter R. Kastl, said the results undercut one of the central access arguments driving surgical scope expansion.

“We calculated the exact driving distances from every isolated optometric practice to the closest ophthalmology office and found these distances are, in fact, relatively small,” said Dr. Kastl.1 “Our results do not support the assertion that patients must travel unreasonably far for specialist eye care. Policy decisions on scope of practice should not rest on that premise.”

READ MORE: An Optometrist’s POV on Glaucoma Management

Truly isolated optometry practices, like those without an ophthalmologist within driving range, are now rarer than ever, just 18 nationwide. Most are tucked into corners of Alaska, Hawaii and Martha’s Vineyard.1

The data at the center

To visualize the nation’s evolving eye care footprint, the Tulane team mapped the entire system: every zip code, practice and mile. Using the Doctors and Clinicians National Downloadable File (June 2014 and June 2024), the Google Maps Geocoding API and the Open Source Routing Machine, they charted true driving routes rather than straight-line estimates.1

The numbers tell a story of redistribution, not decline. Ophthalmology practices grew from about 20,700 to 33,000, a 60% jump, while individual ophthalmologists declined slightly by about 1%. Optometry practices expanded from roughly 32,000 to 46,000 (up by 44%). Meanwhile, isolated OD-only zip codes fell by nearly 7% and average travel distances dropped by 8%.1

Together, these shifts show that while the U.S. may have fewer ophthalmologists, they’re spread farther and wider, reaching communities that once relied solely on optometry for primary eye care.

READ MORE: Little Optometrists, Big Pond

Two professions, one map

Since 2014, seven more states (Alaska, Arkansas, Colorado, Mississippi, South Dakota, Virginia and Wyoming) have joined the ranks of those granting optometrists limited surgical authority, alongside Oklahoma, Louisiana and Kentucky.2 The argument is familiar: too few ophthalmologists, too many miles to drive. But new data tell a different story.

The JAMA Ophthalmology study shows that ophthalmologists’ practice footprints are widening even as their headcount remains stable.1 Meanwhile, optometrists now outnumber ophthalmologists roughly three to one and 99% of Americans live in a county with at least one OD.1,5

It’s a curious paradox: optometrists have never been more numerous, yet ophthalmologists have never been more within reach. Subspecialty surgeons, particularly in cornea, glaucoma and retina, remain concentrated in cities, leaving pockets of rural undercoverage.1,5 Still, the broader trend points toward overlap rather than isolation, with ODs and MDs increasingly sharing the same map.

On the ground: access by air, snow and time

On paper, the distance gap is closing. On the ground, the roads still tell another story.

In Wyoming, optometrist Dr. Roger Jordan, has watched patients drive more than 100 miles for cataract or retina surgery. “People are willing to travel if they need to,” he said, “but snow and age don’t mix well.” His experience mirrors national trends showing that even as average access improves, rural regions still face seasonal and logistical barriers.1,2

Dr. Jordan also notes that collaboration makes the system work. “Our referral relationships are strong,” he said. “We can manage most primary eye care locally, and when patients need surgery, we know exactly where to send them”.2

Strategic implications for policymakers

As access-based arguments lose traction, the next policy debates may hinge less on miles and more on mastery, specifically how training, safety and patient outcomes define surgical authority.2,3

Workforce models project a 12% decline in the ophthalmology supply by 2035, even as demand climbs 24% from aging populations and chronic disease.2 The Tulane findings suggest that smarter distribution of MD practices, not expanded surgical privileges, may be the more effective fix.1

The researchers point to several levers: increasing residency slots, incentivizing rural practice and scaling teleophthalmology to manage chronic eye conditions remotely.2 Collaboration is key, but geography alone no longer explains who gets care or who should provide it.

Shared vision for the future

The data sketch a new portrait of U.S. eye care: two professions converging on the same map, each filling the gaps of the other. Ophthalmologists are reaching farther, optometrists are taking on broader roles and patients are traveling shorter distances than ever before.

Access issues will always exist in remote corners of the country, but the argument that distance drives surgical necessity is losing sight. Geography may once have drawn the battle lines in eye care, but those lines are blurring. The future of eye care may depend less on dividing roles and more on how both professions collaborate to meet rising demand for vision care, wherever patients live.

Editor’s Note: This content is intended exclusively for healthcare professionals. It is not intended for the general public. Products or therapies discussed may not be registered or approved in all jurisdictions, including Singapore.

References

- Kastl PR, Senot C, Hegde R. Distribution of ophthalmologists and optometrists in the United States, 2014–2024. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2025 Nov 13.

- Knight OJ, Elam AR. The ophthalmology workforce the United States needs. Glaucoma Today. 2025;May/June:19–21.

- Mani S, Russo D, Quinn N. Racial and ethnic diversity trends in optometry and ophthalmology residency training programs. Optom Educ. 2024;49(2):Winter–Spring.

- Reed ST. In rural America, opportunity for optometry amid shortfall of ophthalmologists. AOA News. 2025 Jan 23.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook: optometrists. U.S. Department of Labor; 2024.