The image we all have of the Wild West is a little one-dimensional — this is understandable, given the steady stream of western movies churned out by Hollywood. These usually depict cowboys or pioneers battling for territory with Native Americans: Think John Wayne (permanently smoking a Marlboro cigarette) facing off against a tribe wearing warpaint and feathers. Often, the indigenous inhabitants were painted in the broadest strokes and associated with totem poles, powwows, peace pipes and scalping.

There was, of course, far greater depth and variance to the Native American people. Yet no matter how much Hollywood might try to compensate for its historic inaccuracies, the cultural damage is done and the public perception is fixed. Indeed, most people would find it hard to differentiate in any meaningful way between North America’s original inhabitants and those portrayed in movies.

And so too is the public’s perception of the differences between ophthalmologists and optometrists — if they’re aware of any differences at all. In the lay community, there is considerable ignorance about each, including what each involves. However, we cannot blame cowboys or Hollywood for this … and the huge differences in optometric practice around the world don’t help either.

Separating your Optometrists from your Ophthalmologists

A recap is in order for those who are new to optometry, or perhaps have a slightly foggier mind. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO), the primary difference between an ophthalmologist and an optometrist is that the former are medical doctors who are trained in medical school and receive an MD; ophthalmologists undertake four additional years of specialized training in eye care. On the other hand, optometrists in the U.S. receive an OD degree (or doctorate of optometry) by attending optometry school for four years and are not required to undertake postgraduate training.¹

Now, before you think that this sounds different to the optometry training or education you’re aware of, you may be right. The AAO is, after all, an American organization that is speaking about the training medical personnel receive in the U.S. — most countries have their own education systems and traditions. The Academy’s definitions are perfectly accurate, but different countries have their own routes to becoming an optometrist.

Optometrists who learn their trade in the U.K. for example, study for a General Optical Council approved degree, usually for around three years; this is followed by a 12-18 month probationary period. In Hong Kong, it takes five years of education and training to become a qualified optometrist at Hong Kong Polytechnic University; however, they do recognize qualifications from other countries. In Israel, a country that has become a leading innovator in eye-focused healthcare, there are two schools of optometry that offer four year academic degrees.

Balancing the Local and the International

Can these myriad systems and education processes meet the demands of an increasingly interconnected global discipline — and one that requires every optometrist to possess the same core competencies?

At present, the direction of optometry appears positive, with growing awareness of the differences from ophthalmology and considerably increased communication between clinicians and others thanks to the growth in online events. According to Prof. Peter Hendicott, president-elect of the World Council of Optometry, the optimal future is found at the nexus of balancing local concerns and international standards.

“Optometry needs to ensure that, across the world, it has the relevant competencies that will enable it to broaden its scope to participate most fully in the health care delivery system in a particular country, and also at an international level, aligning with and participating in the international health agenda,” said Prof. Hendicott.

“In many countries, optometry is well prepared for its role in this space and is ready to contribute to the management of this increasing burden of disease. In other countries, a wider role for optometry in improving healthcare outcomes will require legislative change to reflect changes to optometric education to equip future optometrists with the necessary increased skills required to prosper,” he said.

71 Optometrists for 3.2 Million

The challenges Prof. Hendicott refers to are particularly acute in developing nations where general healthcare infrastructure is lacking, with optometry even more so. This is particularly noticeable in Africa, where in some countries the number of optometrists can be counted on a single hand. This is the new frontier, a modern day Wild West for the industry, with serious challenges balanced by the opportunity for growth.

For example, Eritrea, located near the Horn of Africa, is a benighted country even by African standards. It is run as a military dictatorship that has been described as a local version of North Korea, characterized by a cult of personality, human rights abuses and military conscription for nearly all young adults. A difficult environment in which to work in any industry, perhaps even more so in the medical field.

Starting in 2009, a program was launched to provide optometry technician (OT) training over a two year period to bridge the gap of care in Eritrea. Carried out in conjunction with the School of Optometry and Vision Science at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, Practice Scope and Job Confidence of Two-Year Trained Optometry Technicians in Eritrea found that 94 OTs had graduated by the end of 2016, and 71 (75.5%) were involved in the country’s eye care services. Four of six regions in the country lacked the required number of OTs to meet the recommended ratio of 1 refractionist per 50,000 people (in a country of 3.2 million), and many reported they had little experience in dispensing (62.9%), clinical examination of patients (35.7%) and low vision care (4.3%).²

“Education and mentorship is how we can improve optometry practice in developing regions, as well as by providing access to advanced equipment in diagnosing medical and eye conditions, like optical coherence tomography (OCT) and biometry scanning. We can achieve this either via donations or by providing further education,” said Sydney, Australia-based optometrist Dr. Oliver Woo, an expert with more than 22 years of experience. He also pointed out that Wild West-esque frontiers are not just geographic — rather, scientific development also offers a glimpse into undiscovered country, too.

“At the moment, the hottest topic in optometry is myopia management. And we are seeing the development of more effective, scientifically proven products and equipment that enable us to manage myopia with great results. Myopia is a global issue and we are on the frontier of it,” Dr. Woo said.

We are Probably Staring at Screens Too Much

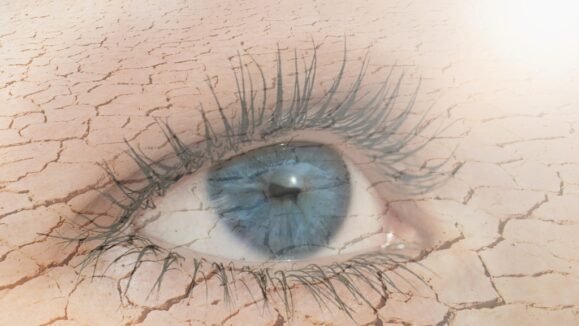

Our glimpse into the education and training of Eritrean doctors highlighted one particular challenge global optometry faces — the exponential increase in myopia is another. Rates have increased so quickly that up to 90% of 18-year-olds in East Asia are myopic and 10-20% are highly myopic. It is estimated that by 2050, the frequency of myopia worldwide will increase to 50% and high myopia to 10%, with high myopia set to become the most frequent cause of irreversible blindness due to its association with myopic maculopathy and glaucomatous optic nerve atrophy.³

Technology is playing a greater role in treating conditions like myopia, as well as preventing them from happening in the first place. We all became familiar with the term “telemedicine” during the COVID-19 pandemic, and while there may be some subject fatigue in this field, there is no doubt that it will play a serious role in optometry in the coming years. This is particularly the case during the diagnosis stage.

“The use of these diagnostic technologies will improve eye care, and coupled with the use of telehealth and the development of lower cost and portable diagnostic technology, this will also increase the reach and availability of high quality eye care across the world,” said Prof. Hendicott.

“This is applicable across all regions of the world. Reduced access to eye care is not just a developing world problem. It happens in populations within developed countries as well,” he added.

It’s Looking Sunny Down Under

There are frontiers — and then there are frontiers — for example, a person living in Eritrea’s capital Asmara may face different troubles compared with a myopic patient from rural China. This does not minimize the problems faced by one individual over another, but rather highlights local specificities and issues. In an increasingly global industry, however, we should consider which regions are getting it right and how they can serve as an example to the wider optometry community.

It is perhaps fitting that this article has taken on something of an antipodean theme as Australia’s collective identity is of a tough, frontier society, the British Empire’s very own Wild West. The country has changed over the years but it still serves as a frontier in optometry, not in its undiscovered potential, but rather as a place that pushes the boundaries of what’s possible. According to Dr. Woo, his country’s optometry experience can serve as a good example for the international community.

“Australia leads the way in the Asia and Pacific region; we have access to many therapeutic and diagnostic products and can provide the best professional eye care to the public. Proper and well-planned tertiary education for optometry, which we have in Australia, is needed in some countries in Asia,” said Dr. Woo.

“Australian optometry can be a role model in practicing optometry for the Asia-Pacific region and beyond, but education and support from the industry are needed to make this profession grow. Also, government intervention and funding are very important to raise the level of optometry and make it become the gatekeeper for many visual-related diseases,” he concluded.

References

- The American Academy of Ophthalmology. Differences in Education Between Optometrists and Ophthalmologists. Available at https://www.aao.org/about/policies/differences-education-optometrists-ophthalmologists. Accessed on Monday, April 12, 2021.

- Gyawali R, Bhayal BK. Practice Scope and Job Confidence of Two-Year Trained Optometry Technicians in Eritrea. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):303

- Jonas JB, Panda-Jonas S. Epidemiology and Anatomy of Myopia. Ophthalmologe. 2019;116(6):499-508. [Article in German]