With a focus on public health, Dr. Priya Morjaria is bridging gaps in eye care for underserved populations around the world

Growing up in a small Tanzanian town, Dr. Priya Morjaria experienced firsthand the struggles of limited access to eye care, which ignited her passion for public health. Now a leading figure in global eye health initiatives, she’s dedicated to improving services for low- and middle-income countries.

Dr. Priya Morjaria, assistant professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), practiced community and hospital optometry for three years before pursuing an MSc in Public Health for Eye Care at LSHTM. She then joined the International Centre for Eye Health (ICEH) as a researcher and later on completed her PhD with a focus on the effectiveness and efficiency of school eye health services.

Today, Dr. Morjaria co-chairs the School Eye Health Working Group at the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness and serves on the World Council of Optometry’s (WCO’s) board of directors as the public health committee chair.

“I grew up in East Africa as a third-generation Indian in a small town called Tabora in northwest Tanzania, living with my grandparents, parents, uncle, aunt, and cousins,” shared Dr. Morjaria. It was a small town with a close-knit community where everyone knew everyone,” she recalled. She later attended an international school in Dar-es-Salaam before moving to the United Kingdom for university—where she now calls home.

A life-long journey begins

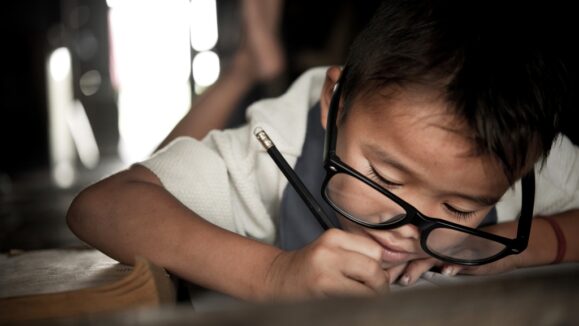

Her decision to pursue optometry was influenced by two significant events in her childhood. “My grandfather went blind after a cataract surgery that went wrong and later developed glaucoma,” she shared. “I have vivid memories of him fumbling around the house, trying to get on with his daily life. Additionally, I was diagnosed with high myopia by the age of five. My teachers wrote to my parents, telling them that I was not paying attention in class and even labeled me as ‘stupid’. One day, I tripped over the teacher’s dog that used to wander into the classroom. It turned out I simply couldn’t see clearly!”

At the time, access to refraction and optometry services was limited, and her family had to travel long distances to replace her glasses—which broke easily. “They were made of glass, and I really didn’t like wearing them,” recalled Dr. Morjaria. “I was teased and bullied, often told nobody that would want to marry a ‘four eyes!’”

While considering a career as a clinical optometrist, Dr. Morjaria also wanted to improve access to eye care for people in low- and middle-income countries. Leaving a well-respected job with a reasonable salary was a risk, but she chose to pursue an MSc in Public Health instead.

“A few months into my program, I realized I really enjoyed learning about public health principles and the importance of evidence-based service delivery. But I had no idea how to turn that into a career until my MSc dissertation supervisor, Prof. Clare Gilbert, saw the potential in me and mentored me,” Dr. Morjaria shared. “Working on various research projects at ICEH exposed me to different countries and experiences,” she added. By then, she realized that her true passion was in research rather than clinical practice.

Tracking children’s eye health

After completing her PhD, she joined Peek Vision, a social enterprise focused on providing sustainable access to eye care in Africa and South Asia. Over the years, her role has evolved, and she is currently the head of Global Programme Design.

“During my PhD, I met Peek’s founder, Andrew Bastawrous, who was eager to implement some of the work that had been done in Kenya focused on tracking children with eye health issues to ensure they receive the care and services they require,” she said. “I wanted to build on the research in Kenya and explore whether educating parents, teachers, children, and their peers would encourage those in need of eye care to follow through with referrals and treatment. Using the software developed by Peek, we tracked these children throughout their journey and sent voice/SMS reminders to parents about their children’s needs. This became the second clinical trial as a part of my PhD,” she shared.

Dr. Morjaria now works closely with the Partnerships and Programmes teams, bringing together the relationships and networks she has fostered over the years with the public health and the clinical standards necessary for effective program designs.

Bridging academia and practice

The year 2017 was particularly memorable for Dr. Morjaria, as she was awarded the prestigious Paul Berman Young Leader Award by the WCO. “I was very honored to be recognized as an ‘expert’ in the field. At that time, there weren’t many optometrists who were both in the academia and also worked in the program field—and that meant I was able to bring both perspectives to important conversations,” she shared. “At the time, I was also trying to find my place in the sector and exploring how I could best contribute to the field of global eye health.”

Indeed, Dr. Morjaria has made school and Leadership (OPAL), which eye health a key focus in her work. Over the past few years, she has been developing and validating a tool from Peek, called School Eye Health Rapid Assessment (SEHRA).

“I realized that while school eye health programs are regularly implemented globally, there are significant gaps in standardization and sustainability. This tool, developed in collaboration with the sector, has been implemented in India, Pakistan, Liberia, and South Africa. We are also planning a national SEHRA in Uganda,” she elaborated.

“The tool consists of two modules: The first investigates environmental factors and the readiness of a are more common than we location to implement a school eye health (SEH) program, while the second gauges the magnitude of eye health needs among children. By integrating these modules, we ensure that the planned program will be tailored and suitable to the environment and address its specific needs. Too often, school eye health initiatives focus solely on refractive errors, neglecting other eye conditions in children,” she explained.

Breaking barriers and navigating challenges

One of Dr. Morjaria’s key leadership roles is serving as chair of the Public Health Committee at the World Council of Optometry. In this position, she works with other optometrists dedicated to public health, advocating for its crucial role in the wider agenda of preventing avoidable blindness and strengthening health systems. As chair, she works alongside regional representatives and committee members on projects that align with the WCO strategy and the global agenda, including supporting the successful Optometry Program for Advocacy and Leadership (OPAL), which fosters future leaders in optometry

worldwide.

Despite a successful career at a relatively young age, Dr. Morjaria acknowledges the challenges and barriers she faced along the way.

“I am a woman of Indian origin who grew up in East Africa,” she said. “When I started in this field, I didn’t realize how gender, ethnicity, and age combined meant I had to work extra hard to have my voice heard or to be taken seriously,” she shared. “I have sat at many meetings where my opinions went unrecognized until someone else echoed the same idea. I know this may sound cliché, but these experiences are more common than we realize, and it’s an issue we haven’t learned to address,” she added.

“Now, as a mother to a seven-month-old son, it’s even more challenging. Like any mother, I want to set an example for him and show that his mummy is strong and confident, but that’s not always easy. I have noticed the subtle perception changes when you attend a meeting with a baby or have a crying infant in the background during a call,” she shared.

Dr. Morjaria believes we still have a long way to go in fully understanding the challenges and barriers faced by women in the workplace, particularly those from minority ethnic backgrounds and younger generations. “On the other hand, I understand the intersectionality of the different factors in many work situations and appreciate the various cultural and language nuances that come into play in many work situations,” she said.

Dr. Morjaria admitted she never fully understood the importance of a work- life balance until she welcomed her baby earlier this year.

“I am guilty of not maintaining a work-life balance for a very long time. But now I consciously plan and make time for it to be the best version for my son. I love running—I have completed four marathons and hope to do a few more, although it feels very challenging at the moment. I also love reading and spending time outdoors,” she enthused.

Small changes, big impact

“Looking back, if I hadn’t had access to an eye test and a pair of glasses at five, I wouldn’t be where I am today,” concluded Dr. Morjaria. “I firmly believe we’re where we are for a reason. So, during difficult times, I remind myself that I am here to make a contribution—however small it is, in the hopes of changing a life.”

Editor’s Note: A version of this article was first published in COOKIE magazine Issue 17.

![iStock 1207202567 [Converted]_V2](https://cookiemagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2022/03/iStock-1207202567-Converted_V2-01-579x326.jpg)