Human stem cell-derived tear gland models reveal a critical cellular process behind lacrimal gland development and function

Dry eye disease (DED) is usually framed in terms of symptoms, severity and surface damage. But as this new study reminds us, the story does not begin at the cornea. It begins deeper inside the tear-producing machinery itself.

New research points to autophagy, the cell’s housekeeping and recycling system, as a central player in lacrimal gland development and function, offering fresh biological insight into mechanisms linked to DED.

Published in Stem Cell Reports, the study shows that when autophagy is disrupted, human lacrimal gland-like organoids fail to develop properly and demonstrate impaired secretory function. The findings connect cellular maintenance pathways to tear gland performance.*

Autophagy and the lacrimal gland

The lacrimal gland produces the aqueous layer of the tear film, and dysfunction at this level is a well-established contributor to dry eye disease. Despite this, the cellular mechanisms that support lacrimal gland development, maintenance and secretion remain incompletely understood.

READ MORE: WCO and Alcon Release New Video on Dry Eye Wheel Use Across Regions

Autophagy plays a key role in cellular homeostasis by breaking down damaged proteins and organelles, allowing cells to recycle components and maintain normal function. While this process has been extensively studied in other tissues, its role in lacrimal gland biology has remained largely undefined.*

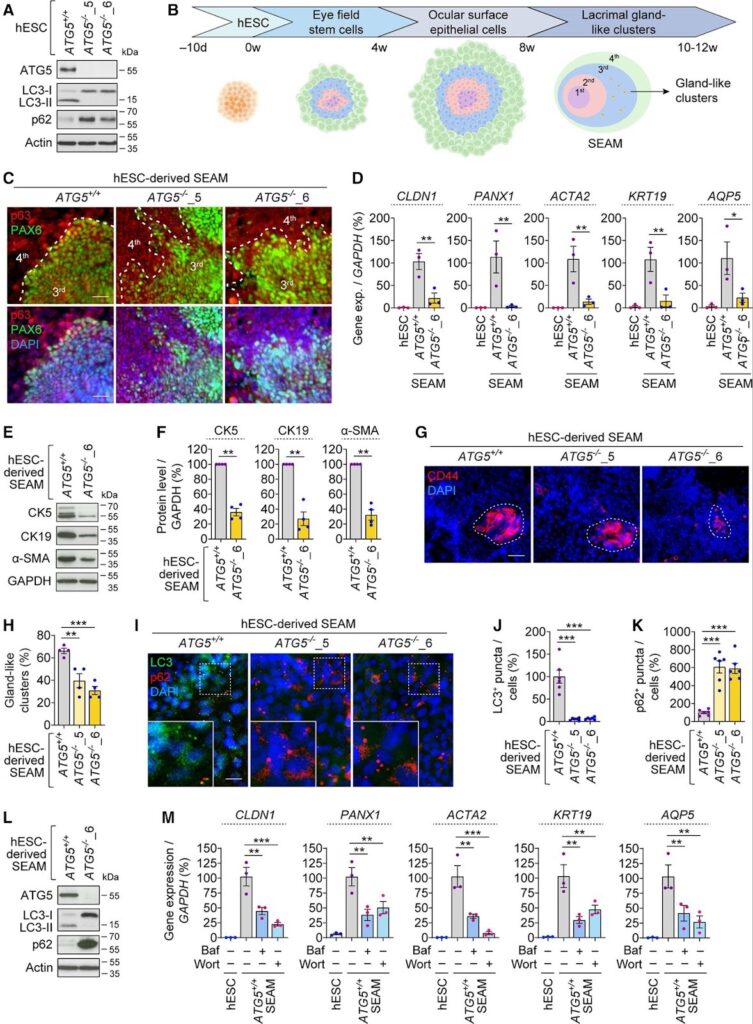

To address this gap, the researchers developed human lacrimal gland-like organoids using human embryonic stem cells (hESCs). These three-dimensional structures recapitulate key features of tear-producing tissue and allow controlled investigation of developmental and functional pathways.

Disabling autophagy disrupts development and secretion

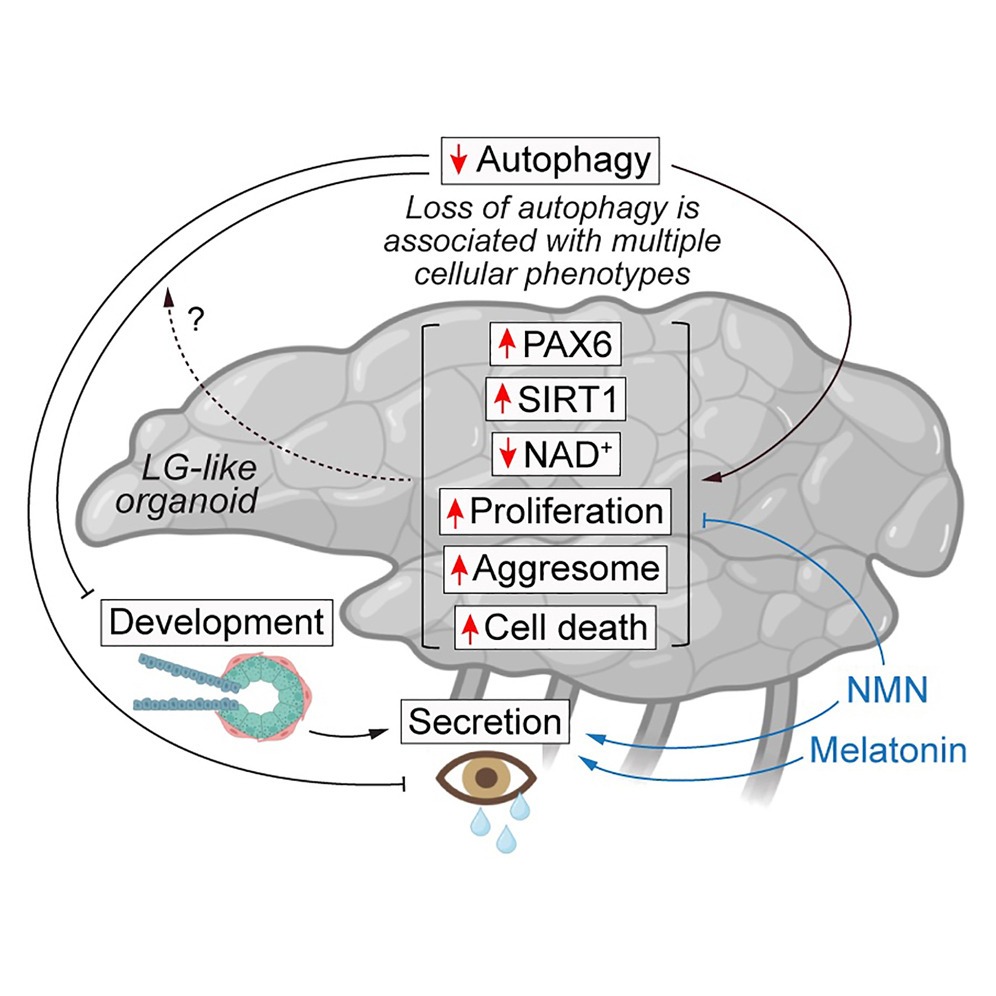

To examine the role of autophagy, the researchers genetically disrupted the process by knocking out the ATG5, a gene required for autophagosome formation. Stem cells lacking ATG5 were then guided through the same differentiation protocol as autophagy-competent controls.*

“Autophagy-deficient LG-like organoids exhibited improper development and secretion, along with increased protein aggregation, proliferation and cell death,” the authors reported.

READ MORE: The FDA Clears Amneal’s Generic Cyclosporine for Dry Eye Disease

Organoids without functional autophagy exhibited abnormal morphology, reduced expression of lacrimal gland markers and diminished production of proteins associated with tear secretion. In contrast, organoids with intact autophagy developed organized gland-like structures and maintained secretory capacity.*

Together, these findings suggest that autophagy is not merely a stress-response mechanism but a fundamental requirement for normal lacrimal gland formation and function.

Cellular stress and protein imbalance

Further analysis revealed that autophagy-deficient organoids accumulated damaged and aggregated proteins and showed increased signs of cellular distress and death. Without autophagy, lacrimal gland cells appeared unable to maintain protein quality control, ultimately compromising tissue integrity.*

The study also identified abnormal accumulation of PAX6, a transcription factor critical for ocular development. Despite reduced gene expression, PAX6 protein levels were elevated when autophagy was impaired, pointing to defective protein clearance rather than increased production.*

These observations reinforce the idea that autophagy plays a routine developmental role by preventing the buildup of proteins that must be tightly regulated for normal tissue patterning.

READ MORE: Study Links Menopause to Higher Risk of Dry Eye Disease

Testing rescue strategies

To further define the role of autophagy, the researchers explored whether secretory dysfunction could be improved after autophagy loss. Autophagy-deficient organoids were treated with nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), a metabolic precursor, and melatonin, a molecule with known regulatory and antioxidant properties.

Both interventions showed measurable improvements in secretion-related outcomes. According to the authors, treatment with NMN or melatonin improved secretory dysfunction in autophagy-deficient organoids. While neither the compound fully restored normal organoid structure, improvements in secretory markers suggest that targeting downstream pathways affected by autophagy loss may partially compensate for the gland dysfunction under certain conditions.*

Study limitations

The authors noted several limitations. The work relied on stem cell–derived organoids rather than animal models or human tissue, and no lacrimal gland–specific autophagy knockout model currently exists. As a result, the findings will require validation in additional experimental systems before clinical relevance can be firmly established.*

Even so, the organoid platform offers a controlled environment for dissecting molecular mechanisms and testing candidate interventions.

READ MORE: Sight Sciences’ TearCare Shows Lasting Dry Eye Relief in Sahara Phase III Trial

The takeaway

The researchers suggest that lacrimal gland–like organoids could become a valuable tool for future ocular surface research, including drug screening and mechanistic studies of tear gland disorders.

Clinical applications may still be a long way off, but this study adds an important piece to the dry eye puzzle.

Editor’s Note: This content is intended exclusively for healthcare professionals. It is not intended for the general public. Products or therapies discussed may not be registered or approved in all jurisdictions, including Singapore.

*Kocak G, Korsgen ME, Amores LF, et al. Autophagy is required for the development and functionality of lacrimal gland-like organoids. Stem Cell Reports. 2025:102744.